Michelangelo, da Vinci, Van Gogh and company were pretty brilliant at hiding secret messages in their paintings

10 Secret Messages Hidden in World Famous Paintings

God’s brainy entourage

There’s a scientific secret hiding in one of the most famous paintings of all time. It resides on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, painted by Michelangelo, as God gives Adam the first spark of life. The flowing reddish-brown cloak behind God and the angels is the exact same shape as a human brain. Researchers have even been able to pick out certain parts, like the vertebral artery (represented by the angel right beneath God and his green scarf) and the pituitary gland.

There are multiple theories as to why Michelangelo might have done this. One suggests that the brain represents God imparting divine knowledge to Adam. A more popular theory, however, suggests that Michelangelo painted the brain in a covert protest of the church’s rejection of science.

How very un-angelic

An angel with attitude can also be spotted on the Sistine Chapel ceiling. The pope who commissioned the work, Pope Julius II, was disliked by many people, including Michelangelo. The artist decided to take a subtle dig at his unpopular patron by painting the prophet Zechariah to look like him, making this section of the masterpiece among the funniest paintings ever for those in the know.

One of the angels behind Zechariah/Julius is making an old-fashioned snarky hand gesture called “the fig” in his direction (for those of you interested in bringing it back, it looks a lot like “got your nose”).

The secretive man in the mirror

Fifteenth-century artist Jan van Eyck couldn’t resist sneaking himself into his famous “Arnolfini Portrait.” In a not-so-secret act of self-promotion, van Eyck wrote “Jan van Eyck was here, 1434” on the wall in Latin behind the two figures. But far less noticeable are the other two figures in this painting.

If you take a close look at the mirror on the wall, you’ll be able to spot two people who appear to be standing about where the “viewer” of this scene would be. It is widely believed that the one with his hand raised is van Eyck.

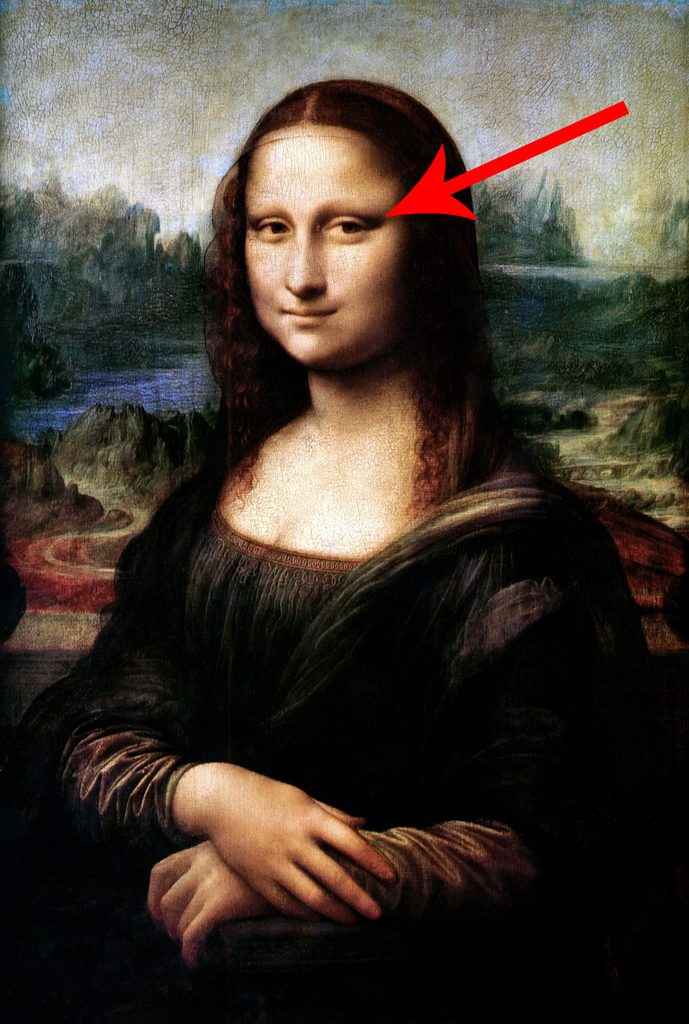

Mona Lisa’s hidden canvas-mate

Though the popular treasure hunt thriller The Da Vinci Code is speculative to say the least, Leonardo da Vinci did hide some secret messages in paintings, including the “Mona Lisa,” which is among the world’s top cultural attractions. This enigmatic lady actually has the artist’s initials, LV, painted in her right eye, but they’re microscopically small.

Even more surprisingly, in 2015 a French scientist using reflective light technology claimed to have found another portrait of a woman underneath the image we see today. The consensus is that this was da Vinci’s “first draft,” and that he painted over it to create his masterpiece.

Botticelli the botanist

As it turns out, the artist best known for “The Birth of Venus” had quite the affinity for plants. Buried in another of his famous paintings, “Primavera,” you can find as many as 500 different plant species, all painted with enough scientific accuracy to make them recognizable, according to researchers.

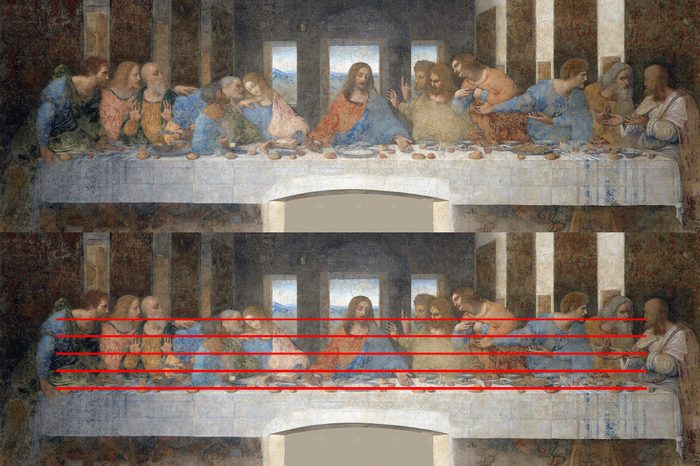

A secret message in the bread

There are theories that Da Vinci’s other world-renowned masterpiece, “The Last Supper,” hints at everything from Christ’s later years to the date the world will end. But one lighter rumor about its hidden clues might actually be true.

Italian musician Giovanni Maria Pala discovered what could very well be a little musical melody written into the painting. If you draw the five lines of the staff across the painting, the apostles’ hands and the loaves of bread on the table are in the positions of music notes. Read from right to left (the way da Vinci wrote), these music notes form a mini 40-second hymn-like melody.

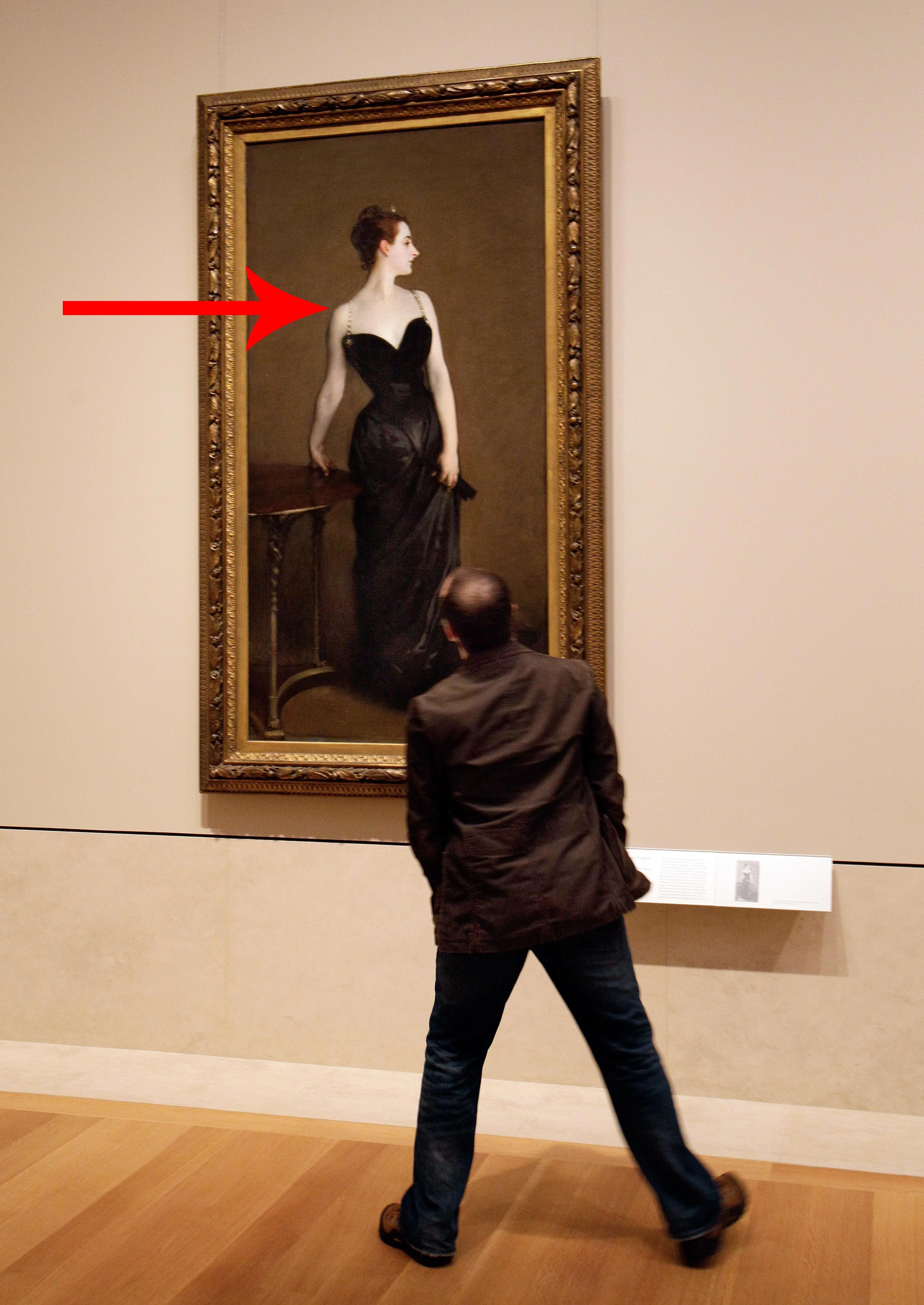

Going strapless = unacceptable

The woman rocking an LBD and immortalized as “Madame X” is actually Virginie Amélie Avegno Gautreau, a Parisian socialite. The 19th-century artist Jon Singer Sargent decided to paint a portrait of her, hoping it would get his name out there. It did … but for all the wrong reasons.

In the original portrait, the right strap of Madame Gautreau’s dress fell down her shoulder. The high-society viewers of the portrait found this mini wardrobe malfunction to be scandalous. Sargent repainted the strap to be in its proper place, but the backlash continued, and he ended up leaving Paris altogether. But this once-scorned painting ended up in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, so things worked out for him.

There’s a secret skull hidden in this room

Some secret messages in paintings require a magnifying glass to spot, while others are large clues that are hiding in plain sight. See if you can find the skull concealed in “The Ambassadors” by Hans Holbein the Younger. Nope, you won’t need special equipment to spy this one. The clue is actually big—but an optical illusion of sorts. Don’t believe us? That beige-and-black diagonal blob at the bottom of the work becomes a skull if you look at the painting the right way. Take a look from the bottom right or left of the image, and see if the skull comes into focus.

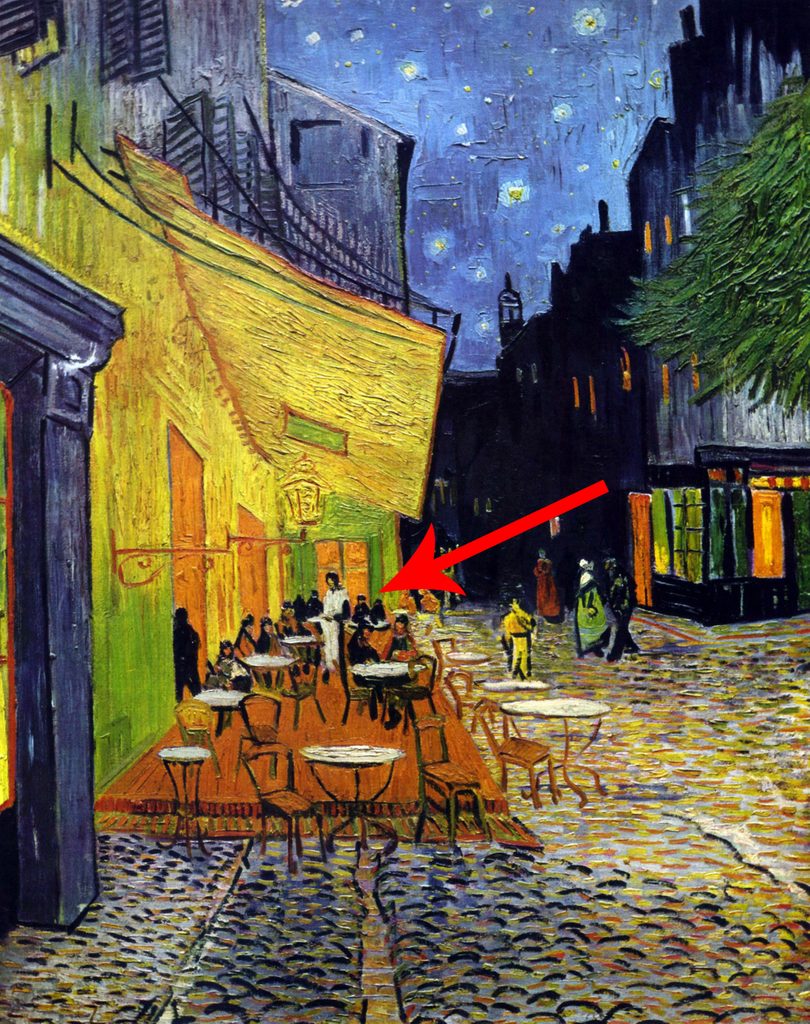

The other Last Supper?

Vincent Van Gogh, the artist behind the famous paintings “The Starry Night” and “Self-Portrait,” also produced this colorful painted café scene, “Café Terrace at Night.” It may be more than just a simple depiction of diners, though. Many clues point to this painting being a more modern riff on da Vinci’s “Last Supper.”

For one thing, Van Gogh was very religious, and his father was a minister. The image also features exactly 12 people sitting at the café. They surround a standing, long-haired figure who just so happens to be standing in front of a cross-like shape on the window.

Drowning your sorrows in wine was never so artsy

Caravaggio’s portrait of Bacchus, the Roman god of wine, is another example of how some hidden clues and art mysteries only reveal themselves with time. In 1922, an art restorer was cleaning up the canvas of this 1595 work. With the centuries of dirt buildup gone, you can see a hidden self-portrait. In the glass wine jug in the bottom left-hand corner, an itty-bitty Caravaggio sits in the tiny light reflection on the surface of the wine.

Why trust us

At Reader’s Digest, we’re committed to producing high-quality content by writers with expertise and experience in their field in consultation with relevant, qualified experts. We rely on reputable primary sources, including government and professional organizations and academic institutions as well as our writers’ personal experiences where appropriate. We verify all facts and data, back them with credible sourcing and revisit them over time to ensure they remain accurate and up to date. Read more about our team, our contributors and our editorial policies.

Sources:

- Scientific American: “Michelangelo’s Secret Message in the Sistine Chapel: A Juxtaposition of God and the Human Brain”

- The Art Crime Archive: “Subversive Messages in the Sistine Chapel”

- The National Gallery, London: “The Arnolfini Portrait”

- BBC: “Hidden portrait ‘found under Mona Lisa’, says French scientist”

- Mental Floss: “15 Things You Should Know About The Birth Of Venus”

- Artnet: “Sandro Botticelli’s ‘Primavera’ Is a Mysterious Celebration of Spring. Here Are 4 Things You May Not Know About This Enigmatic Marvel”

- The Independent: “Musician Finds Hidden Hymn in Da Vinci Work”

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art: “Revealing Madame X”

- The National Gallery, London: “The Ambassadors”

- Van Gogh Studio: “Did Van Gogh Mean to Paint the Last Supper?”

- Art-Test: “Caravaggio: discovery of self-portrait in Bacco“